Explaining exercise

New campus initiative fosters interdisciplinary study of how physical activity promotes good health.

We all agree that physical activity is good for us, so UC Irvine scientists, physicians, nurses, engineers, athletes and dancers are getting together to help answer questions about how exercise really does influence health.

To enable this, the campus has created the Exercise Medicine & Sport Sciences Initiative, which is uniting those who share an interest in fields associated with exercise and sport sciences, exercise medicine and rehabilitation.

A common goal among the myriad researchers who have signed on is to look deeper into exercise’s impact on the human body – studying what it does at the cellular level to modulate body function and how it can be most effectively applied to children and adults living with injuries, diseases or developmental disorders.

“This is the right place and the right time for this,” says James Hicks, initiative director and associate vice chancellor for research at UC Irvine. “For more than a decade, diverse groups of faculty representing six schools here have centered their research on physical activity. The initiative will draw together these core groups to elevate their efforts and improve our understanding in this increasingly important area.”

Along with providing research support, the initiative fosters education and community outreach. The Francisco J. Ayala School of Biological Sciences has created an undergraduate degree program in exercise sciences. “It will be an elite, hard-science program intended to develop a small, highly talented pool of students who’ll become the future leaders that better explore the connection between physical activity and health,” says Hicks, also a professor of ecology & evolutionary biology.

Additionally, the initiative has forged research partnerships with UC Irvine Athletics, the Special Olympics Young Athletes program and USA Water Polo.

More than two dozen individuals affiliated with the initiative are conducting an array of studies on such topics as bone mechanics, the cellular changes of muscles at work, exercising for successful brain aging and functional recovery after stroke.

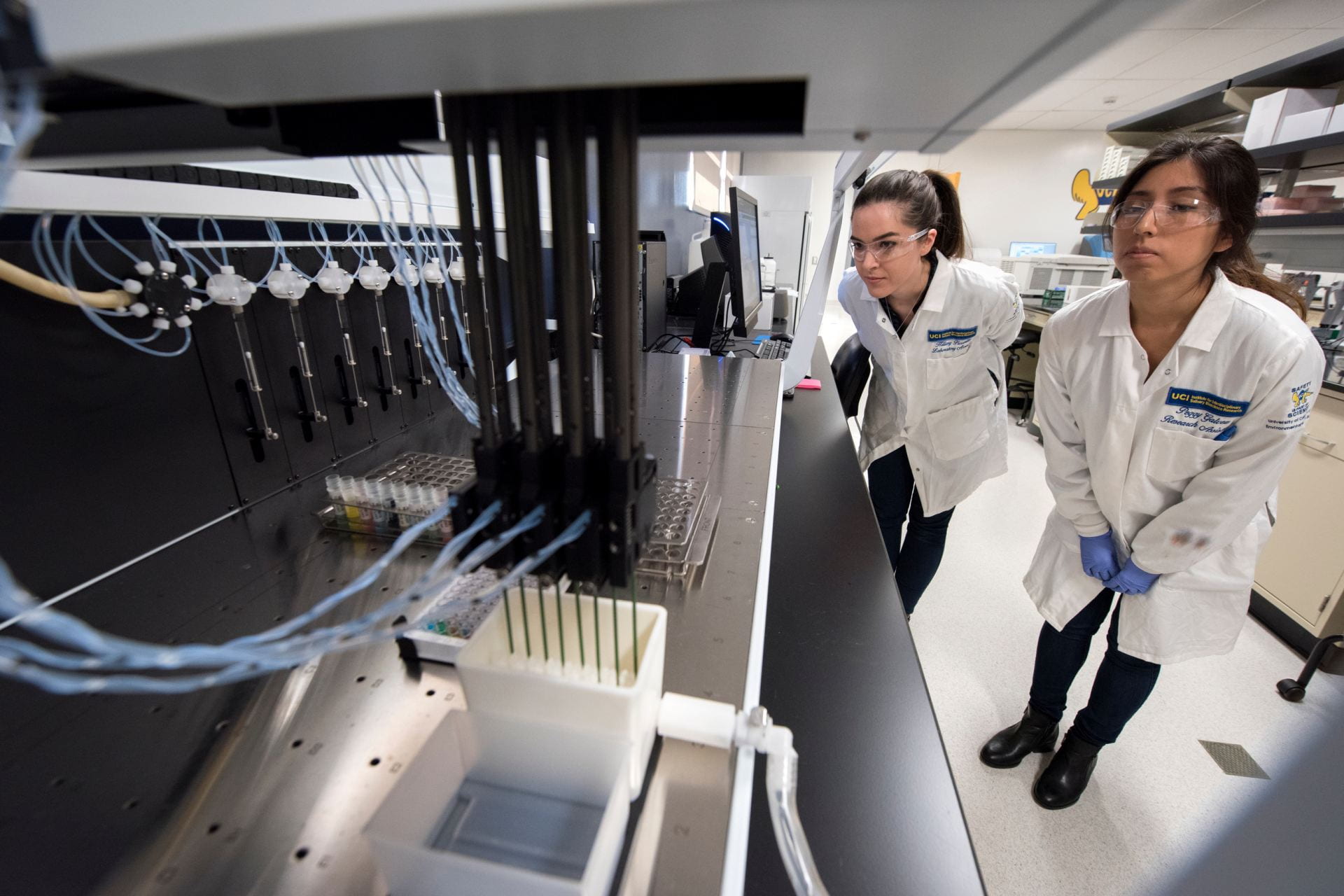

Some of these people are also active in one of UC Irvine’s most established activity-based research programs, the Pediatric Exercise Research Center, led by Dr. Dan Cooper, professor and chair of pediatrics and director of the Institute for Clinical & Translational Science.

PERC sheds light on the full benefits of physical activity. At any one time, it hosts 15 to 20 studies of how – and how much – exercise works to avert Type 2 diabetes, limit asthma attacks, thwart arthritis, prevent cancer, encourage mineralization in growing bones, and improve the quality of life for kids with chronic diseases and congenital disorders.

“In children, exercise is not just play. It’s integral to growth and development,” Cooper says. “The work we do with children is useful in lifespan research. Take osteoporosis, for instance. It has a basis in childhood through the amount of activity [one engages in] at a young age. What you do as a child has a profound impact when you’re 65.”

He sees the Exercise Medicine & Sport Sciences Initiative producing a community of scholars who will build collaborations and connections that are normally hard to make, especially among bench scientists and physicians involved with human studies.

To foster such partnerships, Cooper says, the Institute for Clinical & Translational Science will provide vital clinical research support to the new initiative. Created in 2010 through a $20 million Clinical & Translational Science Award from the federal government, the ICTS is the centerpiece of the campus effort to accelerate the transformation of scientific discoveries into medical advances for patients.

Why the scientific study of exercise?

Hicks, whose own research looks at the evolution and function of oxygen transportation in the cardiac system, notes that physical activity causes unique reactions in a broad spectrum of human cell types, tissues and organ systems. It seems self-evident that exercise promotes good health, but it’s still not clear how it affects specific diseases and conditions.

Without this knowledge, the appropriate use of exercise as therapy will remain imprecise, and the effectiveness of physical activity as a means to benefit human health and wellness may never be fully realized.

Motivating individuals to engage in regular exercise, Hicks says, also remains a challenge that requires systematic research and identification of evidence-based strategies for successful behavioral change.

“I don’t think there are too many things besides physical activity that offer such a wide array of positive results,” adds Vincent Caiozzo, UC Irvine professor of orthopedic surgery. “Exercise can be seen as a very inexpensive medicine to prevent diabetes and a host of other ailments. One of our aims with the Exercise Medicine & Sport Sciences Initiative is to understand what the real payoffs of exercise are and how we can properly ‘prescribe’ it, like a medicine.”